what is a workhouse and why were people forced to live there

Introduction

The Oxford Dictionary's commencement record of the word workhouse dates dorsum to 1652 in Exeter — 'The said house to bee converted for a workhouse for the poore of this cittye and also a house of correction for the vagrant and disorderly people within this cittye.' However, workhouses were effectually even before that — in 1631 the Mayor of Abingdon reported that "wee haue erected wthn our borough a workehouse to sett poore people to worke"

State-provided poor relief is often dated from the end of Queen Elizabeth'south reign in 1601 when the passing of an Act for the Relief of the Poor made parishes legally responsible for looking after their own poor. This was funded by the collection of a poor-rate tax from local belongings owners (a revenue enhancement that survives in the nowadays-twenty-four hour period "council tax"). The 1601 Act made no mention of workhouses although it provided that materials should be bought to provide work for the unemployed able-bodied — with the threat of prison for those who refused. It also proposed the erection of housing for the "impotent poor" — the elderly, chronic ill, etc.

Parish poor relief was dispensed mostly through "out-relief" — grants of money, clothing, food, or fuel, to those living in their ain homes. Yet, the workhouse gradually began to evolve in the seventeenth century equally an culling form of "indoor relief", both to salvage the parish money, and also equally a deterrent to the able-bodied who were required to work, ordinarily without pay, in return for their board and lodging. The passing of the Workhouse Exam Act in 1723, gave parishes the pick of denying out-relief and offer claimants just the workhouse.

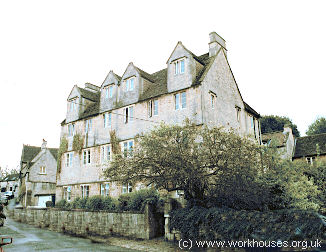

Parish workhouse buildings were frequently just ordinary local houses, rented for the purpose. Sometimes a workhouse was purpose-built, like this one erected in 1729 for the parishes of Box and Ditteridge in Wiltshire.

Parish workhouse, Box, Wiltshire.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In some cases, the poor were "farmed" — a private contractor undertook to expect afterward a parish's poor for a fixed annual sum; the paupers' work could exist a useful style of boosting the contractor's income. The workhouse was not, all the same, necessarily regarded equally place of punishment, or fifty-fifty privation. Indeed, conditions could be pleasant enough to earn some institutions the nickname of "Pauper Palaces".

Gilbert's Act of 1782 simplified and standardized the procedures for parishes to set up and run workhouses, either on their own, or by forming a grouping of parishes chosen a Gilbert Spousal relationship. Under Gilbert's scheme, able-bodied adult paupers would not be admitted to the workhouse, but were to be maintained by their parish until work could be establish for them. Although relatively few workhouses were set up under Gilbert's scheme, the do of supplementing labourers' wages out of the poor rate did become widely established. The all-time known example of this was the "Speenhamland System" which supplemented wages on a sliding scale linked to the price of bread and family unit size. By the start of the nineteenth century, the nationwide price of out-relief was beginning to spiral. It was also believed by some that parish relief had become seen as an easy option by those who did not desire to work. There was also growing civil unrest during this period, culminating in the Captain Swing riots whose targets included workhouses. In 1832, the Government gear up a Royal Commission to investigate the problems and propose changes.

In 1834, the Commission's report resulted in the Poor Law Subpoena Act which was intended to end to all out-relief for the able bodied. The fifteen,000 or so parishes in England and Wales were formed into Poor Law Unions, each with its own union workhouse. A like scheme was introduced in Republic of ireland in 1838, while in 1845 Scotland gear up a separate and somewhat different arrangement.

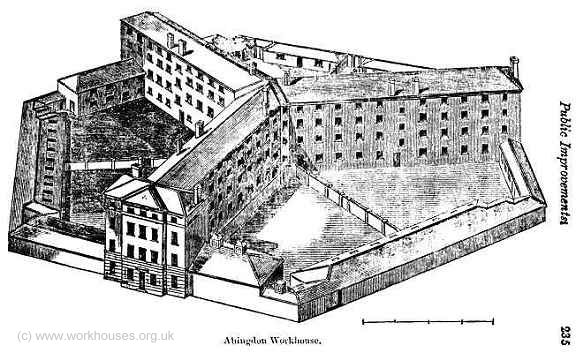

Each Poor Constabulary Union was managed by a locally elected Board of Guardians and the whole arrangement was administered past a central Poor Law Commission. In the belatedly 1830s, hundreds of new union workhouse buildings were erected across the country. The Commission's original proposal to have separate establishments for different types of pauper (the old, the able-bodied, children etc.) was soon abandoned and a unmarried "general mixed workhouse" became the norm. The new buildings were particularly designed to segregate the different categories of inmate. The first purpose-built workhouse to be erected under the new scheme was at Abingdon in 1835.

Abingdon Marriage workhouse, 1835.

©Peter Higginbotham

Under the new Act, the threat of the Marriage workhouse was intended to deed as a deterrent to the athletic pauper. This was a principle enshrined in the revival of the "workhouse exam" — poor relief would only be granted to those desperate enough to face inbound the repugnant atmospheric condition of the workhouse. If an able-bodied man entered the workhouse, his whole family had to enter with him.

Life inside the workhouse was was intended to be as off-putting equally possible. Men, women, children, the infirm, and the able-bodied were housed separately and given very basic and monotonous nutrient such every bit watery porridge called gruel, or breadstuff and cheese. All inmates had to wear the crude workhouse uniform and sleep in communal dormitories. Supervised baths were given once a calendar week. The able-bodied were given difficult piece of work such every bit stone-breaking or picking apart old ropes chosen oakum. The elderly and infirm sat around in the day-rooms or sick-wards with fiddling opportunity for visitors. Parents were merely allowed express contact with their children — perhaps for an hour or so a week on Sunday afternoon.

By the 1850s, the majority of those forced into the workhouse were not the piece of work-shy, but the old, the infirm, the orphaned, unmarried mothers, and the physically or mentally sick. For the adjacent century, the Union Workhouse was in many localities one of the largest and most meaning buildings in the area, the largest ones all-around more than a grand inmates. Inbound its harsh regime and spartan conditions was considered the ultimate degradation.

Matrimony workhouse, Newtown, Montgomeryshire

© Peter Higginbotham.

The workhouse was non, however, a prison house. People could, in principle, leave whenever they wished, for case when work became available locally. Some people, known as the "ins and outs", entered and left quite frequently, treating the workhouse most like a guest-house, albeit one with the most basic of facilities. For some, however, their stay in the workhouse would exist for the rest of their lives.

In the 1850s and 60s, complaints were growing about the atmospheric condition in many London workhouses. Figures such equally Florence Nightingale, Louisa Twining, and the medical journal The Lancet, were particularly critical of the handling of the sick in workhouses which was ofttimes in insanitary conditions and with most of the nursing care provided by untrained and often illiterate female person inmates. Somewhen, parliament passed the Metropolitan Poor Human action which required workhouse hospitals to be on sites separate from the workhouse. The Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB) was also set upwardly to await after London's poor suffering from infectious diseases or mental inability. The smallpox and fever hospitals fix by the MAB were eventually opened up to all London's inhabitants and became the land'due south beginning state hospitals, laying the foundations for the National Wellness Service which began in 1948.

Holborn Matrimony Infirmary, 2003

© Peter Higginbotham.

Towards the stop of the nineteenth century, weather gradually improved in the workhouse, particularly for the elderly and infirm, and for children. Nutrient became a lilliputian more varied and minor luxuries such equally books, newspapers, and even occasional outings were allowed. Children were increasingly housed away from the workhouses in special schools or in cottage homes which were often placed out in the countryside.

Newcastle-upon-Tyne Cottage Homes, Ponteland, 2001

© Peter Higginbotham.

On 1st April 1930, when the 643 Boards of Guardians in England and Wales were abolished and their responsibilities passed to local authorities. Some workhouse buildings were sold off, demolished, or cruel into disuse. Virtually, notwithstanding, became Public Assistance Institutions and continued to provide accommodation for the elderly, chronic sick, unmarried mothers and vagrants. For inmates of these institutions, life ofttimes changed relatively little during the 1930s and 40s. Apart from the abolition of uniforms, and more than freedom to come and go, things improved but slowly. With the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948, many former workhouse buildings continued to business firm the elderly and chronic ill. With the reorganisation of the NHS in the 1980s and 90s, the old buildings were often turned over for use every bit part space or demolished to make way for new hospital blocks or car parks. More recently, the survivors have increasingly been sold off for redevelopment, ironically, in some cases, equally luxury residential accommodation.

Increasingly little remains of these one time neat and gloomy edifices. What does survive often passes unnoticed. But even at present, more than lxx years after its official abolition, the mere mention of the workhouse can withal send a shiver through those sometime enough to remember its existence. In Kendal, the location of a long-gone workhouse is modestly marked in a now renamed side-road. However, some local residents clearly experience this is an establishment they would rather not commemorate...

Kendal route signs, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

For more information virtually every facet of the workhouse, please explore the rest of this spider web-site. If yous can't notice what yous need, endeavour typing a discussion or a phrase (in quotes) into the Search box near the top of any page.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.

mclaughlinruen1959.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.workhouses.org.uk/intro/

0 Response to "what is a workhouse and why were people forced to live there"

Post a Comment